In September 2017, the Social Security Administration sent Gabriel Burgos’ family a letter warning that their income would be cut in half. Gabriel—a Brooklyn high schooler who lived with his mother, Marlena, and father, Jorge, in a public housing apartment—had recently turned 18. That meant the end of the monthly check he got because of his severe learning disabilities.

The family—their names have been changed—was already living in poverty. Three years before, Marlena lost her job as a home health billing clerk; Jorge, due to complications from lifelong diabetes, was unable to work and also collected disability support. The family received food stamps and subsidized rent, but now were facing a future where two Social Security disability checks that once totaled some $1,600 a month would be reduced to $800.

In first grade, Gabriel was diagnosed with severe dyslexia and a central auditory processing disorder that made it hard to read and follow instructions. But after Marlena and a legal aid lawyer got him placed in a specialized school, Gabriel made real progress. “It brought tears to my eyes,” she told me, “when he was in the third grade and was able to pick up a second grade book and read.”

Supplemental Security Income is the federal benefit that provides cash to low-income people with disabilities, including nearly a million children. (It’s a different program from the disability insurance that workers and employers pay into.) In many states, it can be the only lifeline for families with disabled children, especially for those who live roughly at or below the federal poverty level and qualify for full benefits. According to a recent analysis of Social Security Administration data, without SSI, more than 60 percent of recipients would fall into poverty. “SSI is really the program of last resort,” says David Wittenburg of Mathematica, a policy research organization. “If that goes away, you’re not just talking about poverty, you’re talking about extreme poverty for a lot of families.”

About 80,000 kids on SSI turn 18 each year, and, like Gabriel, about half will lose benefits. But the reason isn’t necessarily because their conditions improved; it’s often the result of the government applying a new adult definition. Kids qualify if they have trouble functioning in school, at home, or in their community, while people over 18 are judged only by their capacity to work.

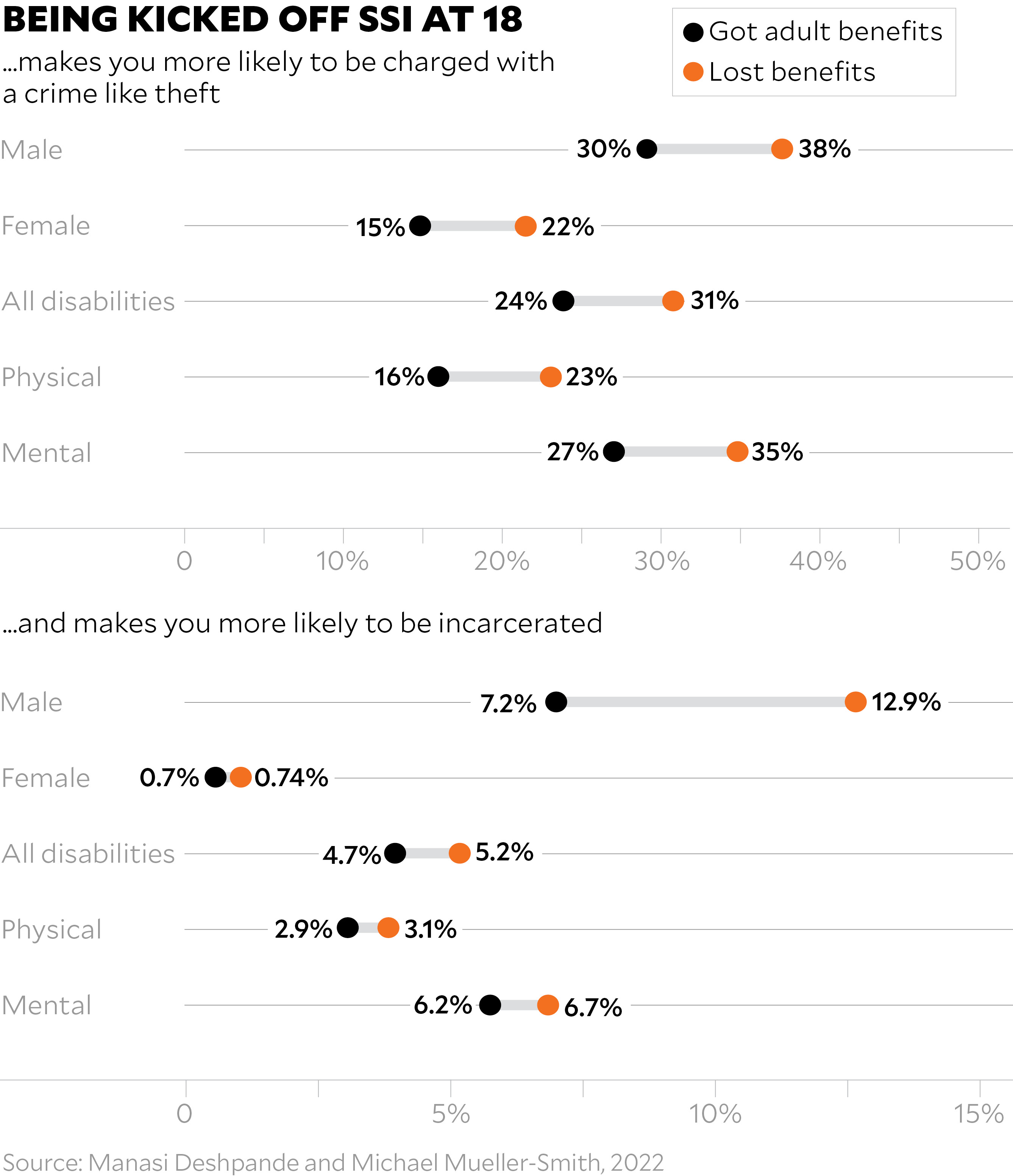

Federal regulations requiring “age-18 redetermination” seem reasonable: Disabilities affect children and families differently than adults, and reassessments can sort out young people who got better. But research shows the consequences can be dire. A study published last year, led by University of Chicago economist Manasi Deshpande, looked back to 1996 when the redetermination policy was first implemented. Using that breakpoint as a massive natural experiment, Deshpande’s team tracked the 20-year trajectories of every child then receiving SSI, merging program data with information on criminal charges and incarceration.

What they found was startling. Youth who lost benefits at 18 were twice as likely to be charged with a crime as they were to hold a job. Compared with those who stayed on SSI, they were 60 percent more likely to be incarcerated. Most were charged with income-generating crimes like theft, fraud, or prostitution. And they didn’t just commit crimes at a higher rate immediately after losing their checks but did so over the ensuing two decades. The study also found that increased spending on policing, adjudication, and incarceration nearly erased any government savings from reduced payouts; the added expenses far outstripped the savings when victims’ costs were included.

Deshpande has also found that beneficiaries removed at 18 who do find work rarely take in enough to escape poverty—earning, on average, as little as a third of what they would have received in benefits. Wittenburg calls Deshpande’s research groundbreaking, and says it should prompt second thoughts about the policy: “You have to rethink this as ‘What are we investing in these children?’ And if we stop investing in them because we think it’s expensive, what are the costs of doing so and essentially kicking them off the rolls?”

Children were not originally meant to be covered by SSI. When Congress created it in 1972 to replace a patchwork of state disability benefits, its focus was on disabled, blind, or elderly low-income adults who hadn’t earned enough to get Social Security disability insurance. A single Nixon staffer who was blind managed to slip in a provision covering kids. It would become the only federal cash benefit explicitly for families with disabled children.

Initially, the only definition of disability weighed impairment against the requirements of any available job; because it was tailored for work-age adults, few children were covered. But in 1984, Congress included mental impairment qualifications, which swept in more kids, and in 1990, a Supreme Court decision gave minors their own process; in six years, the number of children on SSI more than tripled to 954,000.

Amid a handful of specious news stories about parents coaching kids to act disabled and game the system, Congress grew concerned over costs. But audits turned up very little fraud—and research shows that, then and now, fewer kids enroll than are likely qualified. In 1996, Republicans, putting the finishing touches on Bill Clinton’s promise to “end welfare as we know it,” explicitly crafted provisions to make it harder for kids to qualify and requiring reevaluations when they turn 18. The year after the law took full effect, more than 19,000 children aging out were denied adult benefits.

When Gabriel heard his check would end, he was a year from graduating high school, playing sports, and handling classes thanks to federally guaranteed accommodations for extra teacher help. He was reading at only a fourth-grade level. Every morning, Marlena had him make a list of the day’s tasks; she worried he’d get lost in the subway. But a judge denied Gabriel’s adult SSI benefits, ruling he could do “simple jobs.” Marlena doubted any employer would actually remind Gabriel three times to do something. “You know what I’m saying?” she asked. “In the realworld?”

The ecosystem that supports schoolkids with extra test time or help with managing emotions is practically nonexistent in the workforce. If Social Security bureaucrats decide an adult is technically capable of doing some job, any job, they’re usually on their own getting and holding one. While kids who lose benefits are allowed to keep drawing checks as long as they’re in school or vocational training, that program is notoriously hard to navigate and many recipients don’t know it exists. Gabriel’s family didn’t, and though his checks continued through an appeal, after two years it failed and the money stopped.

Despite Deshpande’s statistics, Marlena doesn’t worry about Gabriel getting in trouble with the law, and she believes her son can eventually work and thrive on his own. But she thinks he should have been reassessed later after he had more time to find his footing. “At some point, you have to switch standards,” says Kathleen Romig, the director of Social Security and disability policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, but “I think 18 is too young.” She points to research showing that most people don’t psychologically reach adulthood by that time, adding, “That’s, of course, especially true for kids with intellectual and developmental disabilities” like the majority of those on SSI.

Some experts suggest delaying redetermination to 22, when disabled children age out of educational accommodations, or even 26, when they stop getting parental insurance under the Affordable Care Act. But doing so would take Democrats wanting to expand SSI and being able to overcome a GOP eager to cut benefits and limit eligibility.

For more than three years after Gabriel’s SSI stopped in 2019, he and his parents lived on less than $1,000 a month. “We manage,” Marlena says when I ask how they squeak by. “We’ve always been a family. We always have each other’s back.”

After Jorge underwent triple bypass surgery, his foot turned gangrenous and was amputated. Marlena stayed home to take care of him, while Gabriel took plumbing and carpentry classes. But when Covid came, with no promise of a job, and no benefits to support him while he studied, he decided that continuing to attend wasn’t worth the risk of exposing his immunocompromised dad.

Today, Gabriel helps care for his father full-time. For that work, Medicaid pays him a little more than $300 per week. At 23, it’s the closest he’s come to being employed.