[ comments ]

From business to politics to science, the few get more. What do we do about it?

I recently wrote about how popular culture has become an oligopoly. A shrinking group of franchises and superstars own a bigger chunk of movies, TV, music, video games, and books. For example, before 2000, only about 25% of top-grossing movies were sequels, spinoffs, and remakes. Now it’s usually over 75%.

The thing is, it’s not just culture. Oligopolies are on the rise pretty much everywhere you look.

The story I’m about to tell you is necessarily a bit messy. There’s no such thing as a representative sample of all human endeavors. The data I have range from solid to speculative. How to measure oligopolization, what to measure, and when to start measuring are all good questions with no good answers.

But just about every trend is going in the same direction, and that demands explanation. It’s happened in different places, at different times, and likely for different reasons, but one of the defining features of our era seems to be: the few have more.

And if you feel, as I do, that something big has gone wrong, that there’s a vague taste of poison in the water and in the air, maybe this is why. Maybe that feeling is our souls starving because there’s nothing but remixes on the radio, every business is a subsidiary of a conglomerate, and scientists are stuck rehashing ideas from 50 years ago. (Or maybe it’s uncontrolled anxiety—you might want to get that checked out.)

Here’s the data.

1. A few people make more of the money

Let’s start with the most famous one. You may have heard that income inequality is on the rise, and it is:

But “income inequality” isn’t exactly the right word for this. The Gini coefficient, a measure of overall inequality, has indeed ticked up in the US since the 1980s. But it’s also been pretty flat since 2000 even as the share going to the top 10%, 1%, and .1% has increased. So this isn’t really about the rich getting richer—it’s about the superrich getting superricher.

While we have the best data for the US and Europe, similar things seem to be happening in many other places.

2. A few businesses produce more GDP

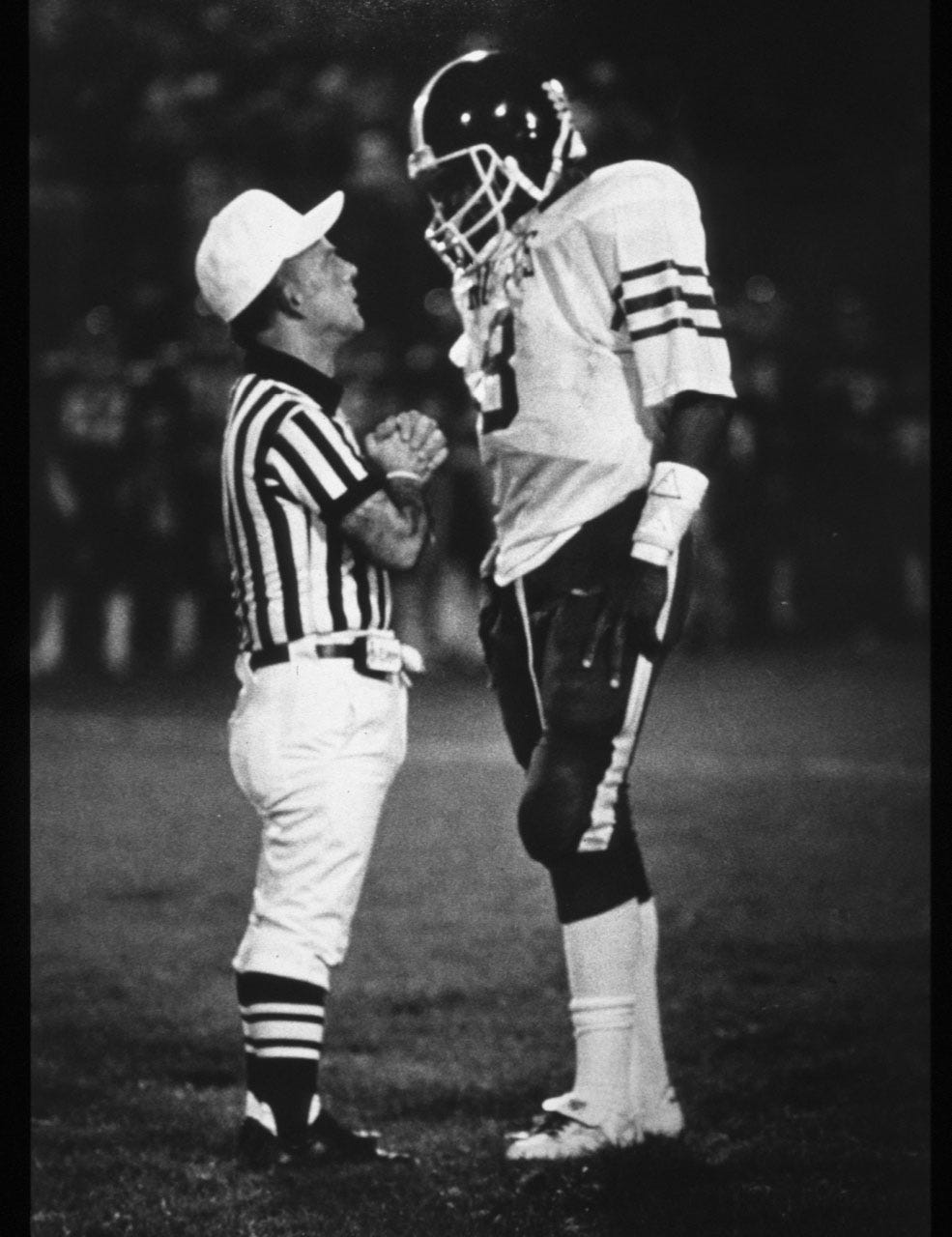

According to FiveThirtyEight, the biggest companies take up a larger share of American GDP:

The Fortune 500 seems to have stayed at roughly two-thirds of GDP since 2013. That may be about as big as the oligopoly can get, since government purchases account for another ~20% of GDP in a normal year.

The rest of the world seems to be following suit. According to VisualCapitalist, the 50 biggest companies made up just 5% of global GDP in 1990; now they make up 28%.

3. A few scientific papers get more of the citations

A healthy scientific field looks like this:

Someone comes up with a useful idea.

People start citing that idea and building on it.

Someone comes up with an even better idea.

People start citing and building on that idea instead.

Alternatively, sometimes an idea is so good and sticks around for so long that people start taking it for granted—you can invoke the idea without citing it anymore. For instance, you can now discuss evolution without including “(Darwin, 1859).”

Unfortunately, this isn’t what happens in science anymore. Instead, as scientific fields continue to grow, more citations flow to the papers that are already cited the most. It is increasingly rare for a new paper to become a highly-cited paper:

(The figure is a little complicated, but the short version is that as fields grow larger, citation inequality grows, and top-cited papers tend to stay at the top.)

If you’re tempted to blame this scientific slowdown on ideas getting harder to find, I have some things to say to you.

4. A few newspapers get more of the readers

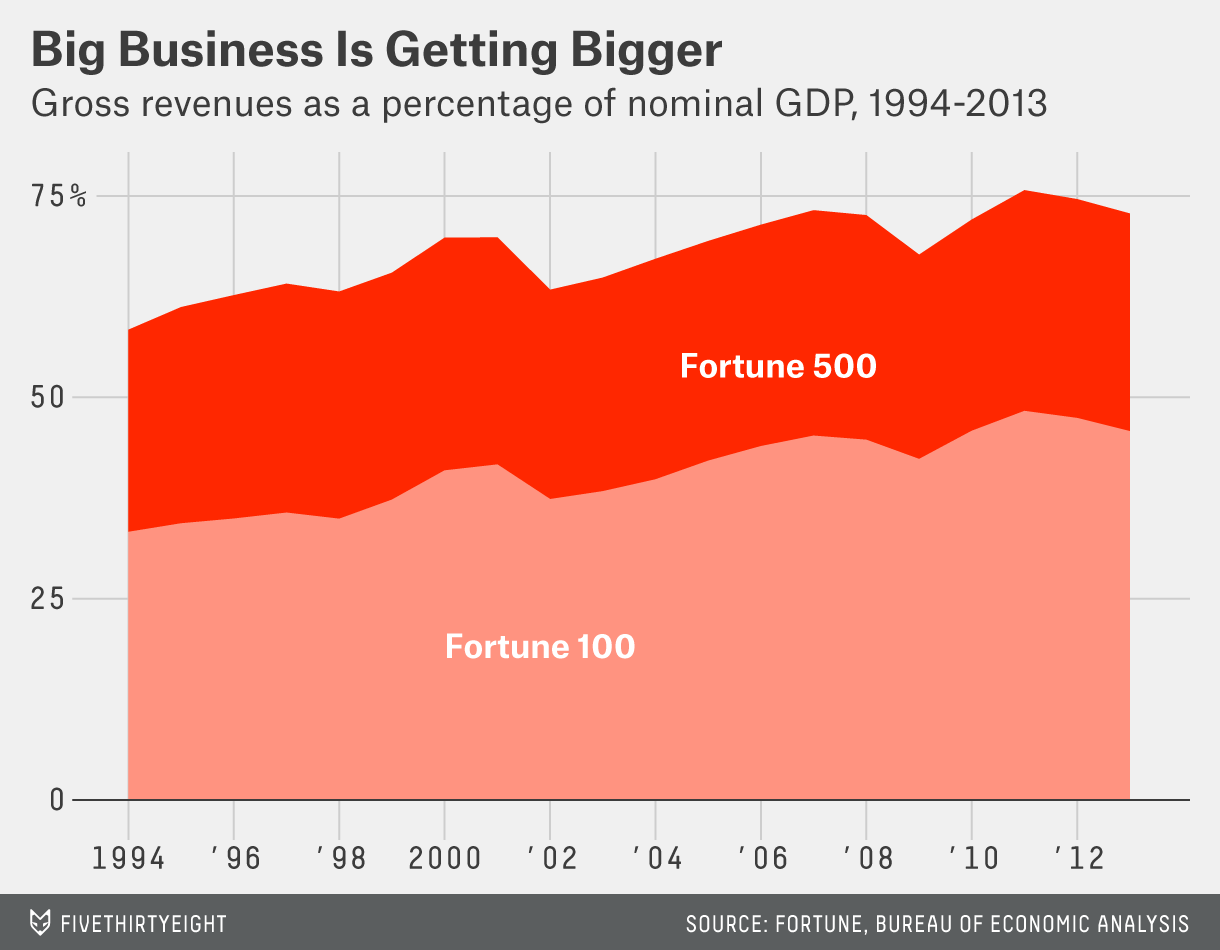

Media companies are a subset of business, of course, but they feel different enough to consider them separately. And news is getting oligopolized, too. Local news has been losing readers:

Meanwhile, business is booming for national newspapers like The New York Times and The Washington Post:

5. A few websites get more of the traffic

The data itself is paywalled so I can’t independently verify it, but this video claims to show traffic to the top 11 sites from 1996 to 2021.

It looks like the oligopoly is online, too. In the early days of the internet, sites flit in and out of the top 11 all the time. Early internet giants—Lycos, Geocities, Netscape—die off. Ask.com and Weather.com come and go. MySpace appears in 2004 and disappears in 2009. But slowly, the chart starts to calcify. Once Google, YouTube, and Facebook assume the top three positions in 2012, they never leave again. In fact, the top 11 has barely changed in the past five years.

6. The two establishment parties now get virtually all of the votes

The US has been a two-party oligopoly for a long time, but sometimes third-party challengers bust in and rack up millions of votes. Has that gotten more or less common over time?

To find out, I collected the results of every American presidential election going back all the way to 1856, the first year that two parties called Democratic and Republican faced off against each other. (The 1856-2012 data comes from Procon.org and more recent data comes from Wikipedia.)

There hasn’t been a major third-party performance for twenty years, and it turns out that’s pretty strange. The only comparably quiet periods came right after the Civil War and just before and after World War II. Otherwise, we haven’t gone more than a few elections without some third-party candidate getting 5% or even 10% of the vote. So it’s surprising that even in 2016, when so many people seemed to find both candidates distasteful, third parties were barely a blip.

Three very long-term trends toward oligopoly

It’s hard to know when to start measuring oligopolization; so far I’ve looked back as far as the data would let me. But there are a few obvious, long-term trends that deserve some attention.

7. A few religions get more of the believers

Once upon a time, there were a whole lot of religions. If you went to the next town over or even next door, you would probably find people worshipping different gods. Now virtually every human on Earth calls themselves Christian, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, Jewish, or non-religious. There’s still huge variation within those denominations, of course. But in the big March Madness bracket of deities, we've reached something like the semi-finals.

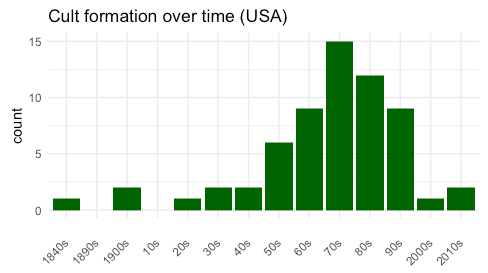

And there’s one more recent, provocative piece of evidence pointing toward further religious oligopolization. Much like third parties in politics, people are always starting new religions—we tend to call them cults. Except, as Roger’s Bacon has shown, there are fewer cults today than there used to be:

8. A few languages get more of the speakers

Most languages on Earth today are disappearing, and that means more people are speaking one of the world’s most popular languages instead. This trend isn’t new, but there’s some evidence it’s speeding up.

9. A few places get more of the residents

Over the past few centuries, humans all over the world have packed up their things and moved to the city. Most people now live in an urban area:

Where does the oligopoly come from?

All of this may seem inevitable. Of course the arc of history bends toward oligopoly—in fact, monopoly is the end state of the universe, and we’re simply on our way there.

I think that’s wrong. When we have data that goes back far enough, we can see that oligopolies can fall as well as rise. Income inequality increased from 1910 to 1930, for example, then declined for forty years before beginning its most recent ascent. The Fortune 500 share of the economy ticked downward during the 2001 and 2008 recessions. Cults exploded in the 60s and 70s and then receded again.

So if oligopolies can wax and wane, why are they waxing now? I’m sure all the usual suspects play a role here: globalization, development, Reaganomics, neoliberalism, capitalism, the internet, algorithms, etc. The Long Peace that began after World War II has provided a Petri dish where oligopoly can grow—the fastest way to spread things out is to blow them up, and we don’t do much of that these days. Some of the explanations I proposed for the pop culture oligopoly apply here as well: choice overload leads people to choose the familiar, first movers can win near-permanent portions of market share, and big things tend to eat, defeat, and outcompete small things, unless something stops them.

Where are the Molotovs?

It’s reasonable to ask, “Where did the oligopoly come from?” And indeed, lots of people are trying to figure out whyinequalityisontherise. But the more important question is, “Why do we allow it to stay?"

After all, we could do something about oligopolies. The government could bust up big companies and tax the rich. People could run for president on third-party tickets and other people could vote for them. Angry mobs could start chucking Molotovs at Amazon warehouses. So why isn’t this happening? When a few players control most of the game, doesn’t it make you want to flip the table?

One possibility is that oligopolies actually aren’t so bad. The tech oligopoly has made the internet way easier to use. Maybe the new scientific papers really aren’t as good as the old ones. And while neither the Democratic Party nor the Republican Party is all that great, they’re at least better than the last third party to ever win an electoral college vote, which ran on a platform of “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

But maybe it’s the olig part of oligopoly that keeps the pitchforks from coming out. Everybody knows monopolies are bad. When there’s one rich guy in town and everybody else is starving, it doesn’t seem that crazy to go smash his windows and steal his food. But when there’s 50 rich guys in town, somehow the state of affairs seems fairer. It’s hard to blame any of them individually; hating “the 1%” is much more abstract than hating Big Rich Jeff Who Owns All the Food. And if there’s a bunch of rich guys, maybe it means you could be a rich guy some day!

Besides, as long as there’s some competition, we avoid the worst parts of a monopoly, right? I’m not so sure. It’s easy to maintain an illusion of competition when there are only a few competitors and they all went to Yale. When one political party offers you a bullet in the head and the other offers you a poke in the eye, the poke may seem so much better than the bullet that you forget to ask why your political system only offers you outrageous choices. Oligopolies may trap us in a region-beta paradox—they aren’t bad enough to overthrow, so we let them make us moderately miserable forever.

Hail, weirdos!

Not all agglomeration is bad, and we shouldn’t send in anti-trust shock troopers the second a company earns a chunk of market share. But with great power should come great skepticism. When businesses get “too big to fail,” you get economic catastrophe. When everybody moves to the city, you get a traffic apocalypse. When there’s only five book publishers, you get endless franchise installments from a guy who is technically dead.

So what do we do about it? We get weird. In an oligopoly, being different is a form of civil disobedience. You can’t pass antitrust legislation all by yourself, and you don’t have a million votes you can give to a third party. But you can spend your money and your time where few other people are spending theirs. You can be a big part of a small audience. The arc of history does not have to bend toward a few having most—we are the ones who bend it.

That’s why I’m worried that we seem to be suffering from a deficit of deviance. In addition to the decline of cults and third parties, signs of counterculture are hard to find. Teens are less likely to smoke, drink, fight, do drugs, or have sex today than they were 30 years ago. This isn’t all bad, but conformity and safety come at the cost of imagination and ambition. Unless you think all of the rules are perfect and all of the important ideas have been discovered, we need some amount of rule-breaking and free-thinking. Without it, the oligopoly closes in on us from all sides.

Of course, not all of us are made to be weird, and that’s fine. If you’re a normie, you can still fight the oligopoly by tolerating weirdness. You can let your kids get really into dark comic books (don’t worry, Mom and Dad, I turned out fine). You can be curious instead of critical when you see someone dressed up like they’re from 18th century Britain or 22nd century Japan. You can give the Mormons at your door a whole ninety seconds instead of the customary three. You don’t have to agree with them, but they deserve your respect. Much like our genetic diversity protects us from pathogens, our social diversity protects us from oligopoly.

So I say: God bless the weirdos. God bless the men who live as dogs. God bless the girl I knew in college who later became a nun. God bless this guy making music in his closet for his 1,099 monthly listeners. God bless the good folks of Port Clinton, Ohio, who celebrate the New Year by slowly lowering a 600-pound fiberglass walleye from a crane. God bless the people who refuse to own a smartphone and the people who speak Klingon. May they never hurt anyone, and may they never be put in charge. But I am proud to share a planet with them. And if they ever disappear, it means the oligopoly has won. So bless them, bless them all.

Ready for more?

[ comments ]